Prelude

Introduction.

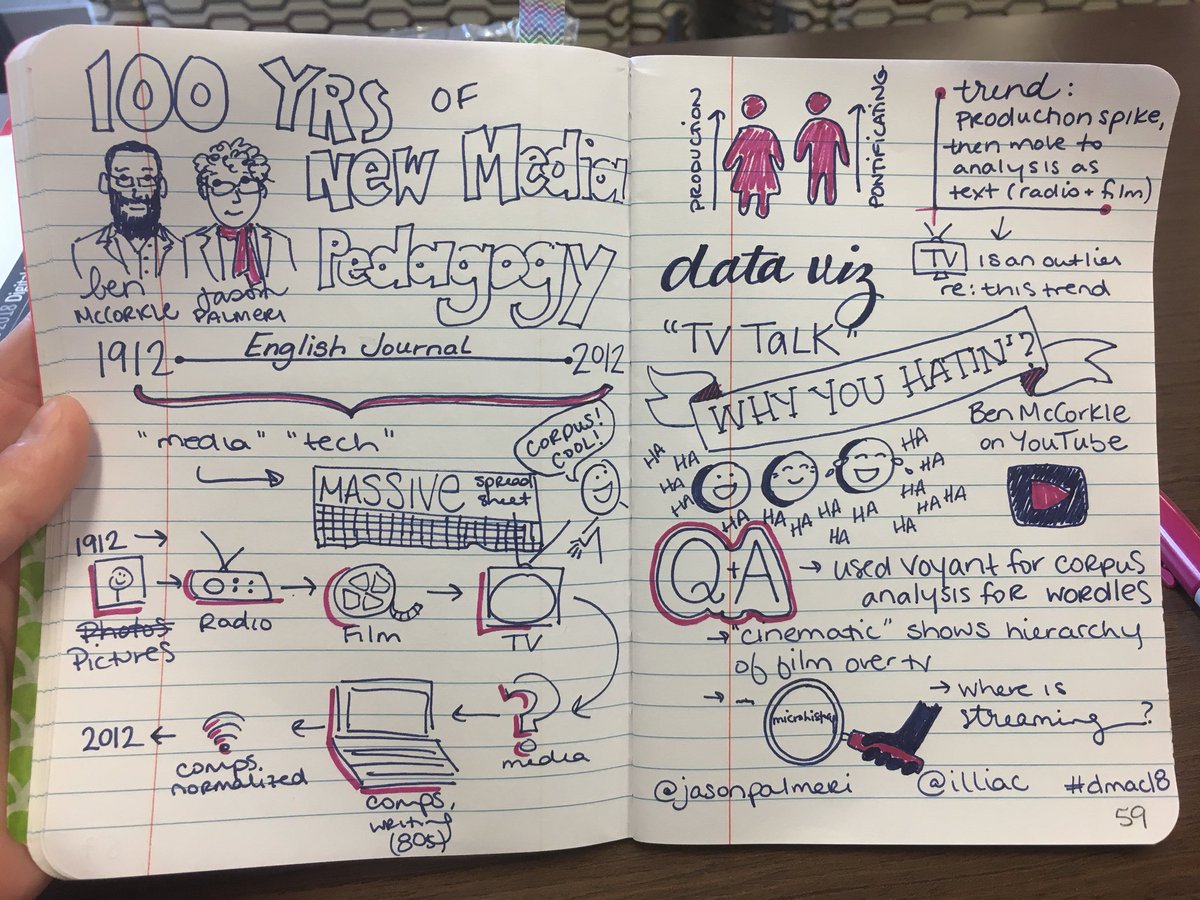

Looking back through the archives of English Journal is akin to studying a petri dish colonized by the wee beasties of technologies past and present. Through the lens of a microscope, one can observe a landscape teeming with magic lanterns, stereoscopes, Super 8 cameras, phonographs, radios, tape recorders, televisions, photocopiers, and typewriters, to name only a few of the older technologies one can find there. Recognizing the diverse, fecund nature of this media ecology, the two of us became inspired to develop an alternative genealogy or prehistory of computers and writing, a look back at how the field—as well as our kith and kin in English studies more broadly—has responded to the presence of communication technologies and media as they emerge, wax, wane, and recede from our collective view over time.

Placing 766 articles from English Journal from 1912 to 2012 in dialogue with other archival materials, 100 Years of New Media Pedagogy reveals common trends and divergences in how English teachers have theorized and practiced new media pedagogy. Moving beyond traditional alphabetic case study approaches to history, this book employs a combination of thin description, data visualization, media archaeology, and multimodal performance methodologies to see English studies’ evolving relationship to new media with fresh eyes. By taking an expansive, 100-year view of media pedagogies in the field, we work not only to recover useful pedagogies for today, but also to enable contemporary scholars and teachers to avoid some of the pitfalls of the past.

Academic fields of teaching and study such as “English” or “Computers and Writing” or “Digital Humanities” do not emerge into the world fully formed, but instead develop over considerable expanses of years and decades. Often, those changes are covered over with the dust of history, making it difficult to understand how we have come to be where we are today. This inevitable process of historical erasure leads to the creation and propagation of unexamined assumptions about the values associated with the discipline—for example, the common notion that the introduction of the personal computer ignited English studies’ interest in multimodal literacy. When we take a long view of the past 100 years of writing about media technology in English Journal, however, we can uncover a substantial history of visual and audio media production pedagogies in the field. We can track moments when media production pedagogies flourished as well as moments when they dwindled, and we can offer theories about why these shifts occurred. We also can track the sedimented ideological topoi about “new media” that have both constrained and enabled innovative media production pedagogies over time. And finally, we can locate individual instances of eyebrow-raising classroom practices, be they either uniquely effective or potentially problematic.

This book argues for a more capacious vision of the diverse origins of the field of computers and writing that engages the rich history of—not only the computer—but media and writing more broadly. Our work also presents an expanded history of the related field of digital humanities by outlining a long pre-digital tradition of English teachers encouraging students to employ new media tools to engage with literary texts. In addition to contending that digital humanists could benefit from a more thorough familiarity with the pedagogically focused research of the computers and writing community over the past 35 years (Reid, 2012; Ridolfo & Hart-Davidson, 2015), we suggest that digital humanists also have much to learn from recovering a much longer pedagogical tradition of English teachers working with students to both analyze and compose a wide range of non-print, multimodal texts.

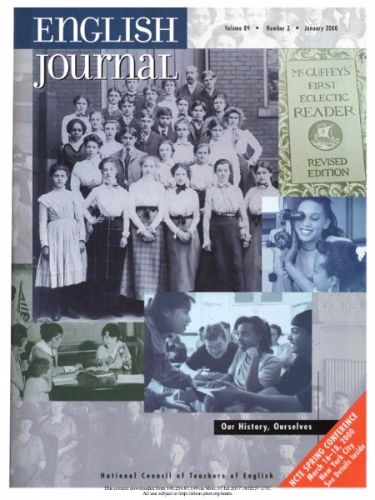

English Journal—in continuous publication since 1912, and covering classroom practice from primary to post-secondary levels—offers us an ideal archive for tracing just how English teachers have adopted, adapted, and innovated with new media over a 100-year span (not to mention how they have occasionally lamented, bemoaned, or abandoned them altogether). Although English Journal does include some discussion of higher education pedagogy, its archive has been largely ignored by university-based digital humanists and computers and writing scholars because of its emphasis on K-12 education. We contend, however, that English Journal’s focus on K-12 education is actually a strength of the archive. After all, we must remember that both the field of composition studies as well as the sub-field of computers and writing formed in part out of dialogue with K-12 educators and university scholars (Hawisher, LeBlanc, Moran, and Selfe, 1996; Stock, 2011). Furthermore, even in a moment when writing departments are increasingly housed separately from English departments (O’Neil, Crow, & Burton, 2002), the teaching of writing remains culturally associated with the disciplinary formation of English in the popular imagination. When students arrive in our first-year writing classes, they tend to conceptualize them as “English” classes—no matter where the courses are located within the university structure. When strangers on an airplane ask what we do, they tend to conflate “writing professor” and “English professor” no matter how we self-identify or where we are institutionally situated. Given the historic and contemporary intersections between the field of computers and writing and the disciplinary formation of English, it makes sense to look back systematically at the ways in which English teachers have engaged with new media and associated technologies over time.

Our work builds on a rich tradition of historical scholarship within the field of computers and writing that has demonstrated the importance of situating contemporary digital writing pedagogies in relation to past teachers' experiments with diverse analog, mechanical, and electronic composing technologies. In their foundational history of computers and writing, Gail Hawisher, Paul LeBlanc, Charles Moran, and Cynthia Selfe (1996) paid substantial attention to how the field was formed collaboratively between composition and rhetoric specialists and K-12 English educators; because the authors focused their attention on pedagogies of the personal computer, however, they began their history in 1979, and thus didn't attend to the longer history of English teachers' engagement with diverse media technologies throughout the twentieth century. Recognizing the importance of recovering the prehistory of computers in writing, a few scholars in the field have begun the work of recovering pre-digital approaches to English pedagogy—engaging such diverse technologies as the pencil (Baron, 2009), the typewriter (Kalmbach, 1996), the chalkboard (Krause, 2000), and the instructional film (Ritter, 2015). We remix this body of work with footage from The Prelinger Archives in the video below:

-

Click to view transcript

Pre-Histories of Digital Pedagogy (.txt version)

[Intro music. Handwriting on screen reads, "Dear audience--The name of this

story is..."]

[Title slide: Pre-Histories of Digital Pedagogy]

Narrator: The teaching of writing has long been a technological act. Today's

digital writing instructor can learn much by revisiting the long history of

technological instruction in both K-12 and university classrooms.

For example, Steve Krause (2000) related the fascinating story of how the

chalkboard moved from a supposedly transformative innovation in 19th century

pedagogies to a "natural," taken-for-granted piece of equipment in nearly all

classrooms. Krause showed that the naturalization of the chalkboard occurred

largely because it supported pedagogical approaches that were already dominant

at the time, most notably the lecture.

In a similar vein, Dennis Baron (2009) recovered the complex ways that the

pencil and the eraser moved from contested new technologies to naturalized

classroom writing devices. Reflecting on teachers who worried that the ability

to erase would destroy literacy as we know it, Baron drew connections between

past arguments about the pencil and contemporary debates about the use of

computers in the writing classroom.

[Transition music]

Moving from pencils to typewriters, James Kalmbach (1996) explored how K-12

teachers in the 1930s moved beyond formulaic typewriting instruction to engage

students in using typewriters for collaborative learning activities and for

composing texts for audiences beyond the classroom. Kalmbach both celebrated

this movement and also demonstrated the ideological forces that caused it to

quickly fade away.

Woman in Instructional Film: In order to become an expert typist, it is

essential to master the correct typing technique. How you type is more important

than what you type.

Narrator: In the end, Kalmbach sounded a cautionary warning that "our current

uses of computer-supported classrooms are both predated by the

typewriter-supported classrooms in the 1930s and framed by similar pedagogical

arguments about the role of technology in education" (p. 66). We think Kalmbach

is right on about how much we have to learn from past failed K-12 media

experiments. And, as we peruse all this footage of women typing, we're reminded

too of Liz Rohan's (2003) and Janine Solberg's (2007) work that has revealed how

gendered constructions of typewriting continue to influence how contemporary

students and teachers engage with computer technologies.

[Transition music]

Turning to the history of instructional film, Kelly Ritter's (2015) recent book,

Reframing the Subject, recounted the problematic ways in which 1940s and 1950s

K-12 English educators employed film viewing to promote "current-traditional"

models of correctness in both writing and social behavior. For example, Ritter

analyzed the classist and sexist literacy assumptions of such instructional

films as this one about social letter writing.

Girl in Instructional Film: I see that there are different letters for different

purposes, and I think I know the purpose of mine. It's a thank-you letter for a

visit.

Boy in Instructional Film: Mmm-hmm.

Girl: But, uh, well, that's what I tried to write, but it's not very good.

[Girl hands letter to Boy; Boy rustles paper.]

Boy: On notebook paper. And torn out. Written in pencil! Hey, you'll want it

neater than that.

[Boy hands letter back to Girl, exasperated.]

Boy: And you better check that spelling, too.

Girl: Read it, please!

Narrator: The history of mansplaining is very old indeed. Importantly, Ritter

argued that the classist and sexist legacies of instructional film live on in

some contemporary approaches to MOOCs that employ video lectures in similarly

problematic ways. While Ritter focused exclusively on teacher-centered

approaches to instructional film in the 1940s and 1950s, this book seeks to

offer a broader view of how English teachers have employed both film analysis

and film production for a range of progressive and conservative ends.

[Outro music. Handwriting on screen reads, "This is the end!"]Media assets used in this production listed in Production Notes.

In addition to the histories we discuss in the video above, other scholars have begun to look specifically to the English Journal archive to historicize contemporary digital writing pedagogies. In "'Making the Devil Useful': Audio-Visual Aids in the Teaching of Writing," Joseph Jones (2012) offered a look back at discussions of multimedia tools in English Journal from 1912 to around World War II—highlighting such diverse technologies as film projectors, stereopticons, phonographs, and radios. Engaging a relatively small number of articles, Jones argued that "secondary school English teachers often claimed audio-visual equipment to indicate a new professionalism, yet descriptions of its uses reveal that innovative technology was often used in retrograde ways" (p. 95). Providing a similar historical critique of how English teachers have approached new technologies, Troy Hicks, Carl Young, Sara Kajder, and Bud Hunt (2012) offered a selective review of English Journal articles about media technology over the past century, which ultimately concluded that "despite all the cultural and technological changes in the types of texts we are able to produce and consume, and the revolutionary predictions we have made, not much has really changed in the teaching of English over the past 100 years" (p. 68). Although we concur in part with the critiques of Jones and Hicks et al. regarding the limiting ways English teachers have sometimes employed media technologies over the years, we extend their case study approaches by systematically coding and visualizing a much larger collection of media-related English Journal articles—seeking to offer a more complex and multivalent vision of both innovative and "retrograde" uses of technology in English studies over a longer period of observation.

This book also contributes to broader interdisciplinary conversations about histories of “new media.” Taking to heart Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey Pingree’s assertion that “all media were once ‘new media’” (2003, xi), we look back to moments in the field when media such as radio or television were new and English teachers explored wide-ranging methods of incorporating them into instruction—often placing new media in dialogue with older print technologies. In this way, 100 Years of New Media Pedagogy contributes to the broader field of media history by documenting how English teachers have played a role in influencing the cultural patterns of “remediation” (Bolter and Grusin, 1999) that have helped people make sense of newly emerging media forms and adapt to them culturally over time. We critically examine, for example, how English instructors often positioned new media as tools to enhance student engagement in print reading and writing—a rhetorical move that both opened up new possibilities for what literacy instruction might entail while also constraining the ability of new media to act as a fully disruptive force in English education.

Re-seeing the history of new media pedagogies at both macro and micro-levels of scale, we complicate and extend common ways of narrating the history of technological pedagogies in English instruction. In particular, our data visualizations (Chapter 3) and multimodal case studies (Chapters 4 - 7) suggest:

- that student media production has long been a part of English pedagogy;

- that moments when media are new present opportunities for pedagogical innovation;

- that, over time, English teachers have framed their engagement with new media through a relatively stable (yet also contradictory) set of ideological assumptions;

- that new media pedagogies have “lifespans” (Selfe and Hawisher, 2004) with predictable patterns;

- that the evolution of computerized pedagogies in the field has differed in important ways from previous “new media” moments;

- that new media pedagogies have long been constrained by corporate logics of control and surveillance;

- that women have long played a leading role in developing and enacting new media production pedagogies in the field.

Although we make and support these tentative claims about the history of new media pedagogy in English studies, we most pointedly do not seek to tell a single or definitive narrative of the history of new media in the field. We ultimately hope that this book provokes more questions than it answers.

Challenging the linear conventions of print history, we showcase a robustly multimodal approach to historical storytelling that simply cannot be contained with the pages of the traditional print codex. As we look back at the various moments in which media production pedagogies have faltered and been abandoned in the field’s past, we speculate that one reason media production pedagogies have not been sustained over time is that English instructors rarely have had the chance to compose scholarship using the new media tools they were teaching students to employ. By composing this history in multimodal, born-digital form, we therefore seek to challenge the print-centric, scholarly conventions that have for too long hindered pedagogical change in our field.

In many ways, the structure of this book is not unlike a mullet: business in the front, party in the back. The serious methodological theorizing of Chapter 2 moves into the quantifiable data visualizations of Chapter 3. Then, in Chapters 4 - 7, we let our hair down a bit and present a series of performative multimodal case studies on audio , cinematic, televisual, and computer pedagogies that are composed in a wide range of multimodal genres—podcasts, silent films, 80s public access call-in programs, and GeoCities-style websites, to name but a few. Lastly, in our Coda, we outline the key takeaway points of the book, using a range of contemporary internet genres.

Review

Manuscript prepared for

Review

Manuscript prepared for